Swimmer’s Itch

Prevention is key to itch-free enjoyment of the water!

The Glen Lake Association is a leader in swimmer’s itch research and education. We are committed to helping area residents and visitors understand what swimmer’s itch is and what can be done to prevent it. Fortunately, only less than one in three people are affected by it, and it’s almost entirely preventable!

PLEASE HELP US BY REPORTING SWIMMER’S ITCH!

The Glen Lake Association partners with the international North American Swimmer’s Itch Reporting Network to better predict and understand swimmer’s itch. We encourage everyone who experiences a reaction to report it using the button below. Be sure to both report and map your “itch.” This data is invaluable to our continued study of swimmer’s itch prevention strategies.

Swimmer’s Itch FAQs

Q: What is swimmer’s itch?

A: Swimmer’s itch, also called cercarial dermatitis, appears as a skin rash caused by an allergic reaction to certain parasites that infect some birds and mammals. These microscopic parasites are released from infected snails into fresh and saltwater (such as lakes, ponds, and oceans). While the parasite’s preferred host is the specific bird or mammal, if the parasite comes into contact with a swimmer, it burrows into the skin causing an allergic reaction and rash. Swimmer’s itch is found throughout the world and is more frequent during summer months. Most cases of swimmer’s itch do not require medical attention. -Source: CDC

Q: What are the signs and symptoms of swimmer’s itch?

A: Symptoms of swimmer’s itch may include: tingling, burning, or itching of the skin; small reddish pimples; or small blisters. Within minutes to days after swimming in water containing swimmer’s itch parasites, you may experience tingling, burning, or itching of the skin. Small reddish pimples appear within twelve hours. Pimples may develop into small blisters. Scratching the areas may result in secondary bacterial infections. Itching may last up to a week or more, but will gradually go away. Source: CDC*

Q: Who is at risk for swimmer’s itch?

A: Anyone who swims or wades in water containing swimmer’s itch parasites may be at risk. Larvae are more likely to be present in shallow water by the shoreline. Children are most often affected because they tend to swim, wade, and play in the shallow water more than adults. Also, they are less likely to towel dry themselves when leaving the water. –Source: CDC*

Q: Is swimmer’s itch contagious?

A: Swimmer’s itch is not contagious and cannot be spread from one person to another. Source: CDC*

Q: Do I need to see my health care provider for treatment?

A: Most cases of swimmer’s itch do not require medical attention. If you have a rash, standard anti-itch treatments may be utilized to relieve the affected areas. Though difficult, try not to scratch, as scratching may cause the rash to become infected. Source: CDC*

Q: How does water become infested with the parasite?

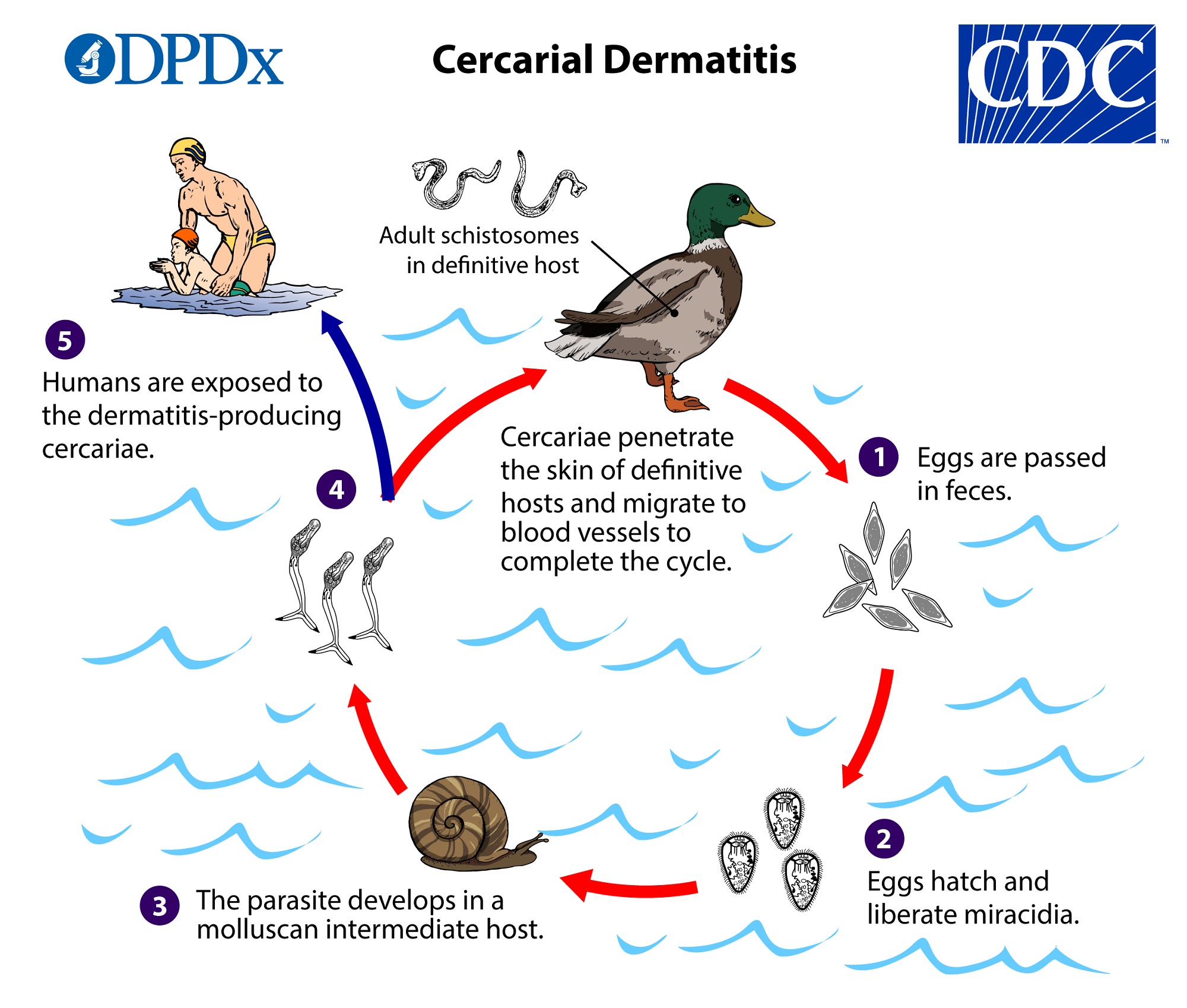

A: Glen Lake is the home of three bird species currently known to be parasite hosts: Mallard Ducks, Canada Geese, and Common Merganser. According to the CDC*:

“The adult parasite lives in the blood of infected animals such as ducks, geese, gulls, swans, and certain mammals such as muskrats and raccoons. The parasites produce eggs that are passed in the feces of infected birds or mammals

If the eggs land in or are washed into the water, the eggs hatch, releasing small, free-swimming microscopic larvae. These larvae swim in the water in search of a certain species of aquatic snail.

If the larvae find one of these snails, they infect the snail, multiply and undergo further development. Infected snails release a different type of microscopic larvae (or cercariae, hence the name cercarial dermatitis) into the water. This larval form then swims about searching for a suitable host (bird, muskrat) to continue the lifecycle. Although humans are not suitable hosts, the microscopic larvae burrow into the swimmer’s skin, and may cause an allergic reaction and rash. Because these larvae cannot develop inside a human, they soon die.”

Worried about swimmer’s itch?

Prevention is key!

If you’re one of the unlucky ones with an allergy to the parasite causing swimmer’s itch, you may avoid exposure by taking a few simple precautions. If carefully employed, these methods will work to greatly reduce or even prevent swimmer’s itch for the swim season. Please note that these strategies should be used together to be most effective.

how to Prevent Swimmer’s Itch:

- Cover your skin with full body swimwear – swimmer’s itch rarely affects hands, feet, and face

- Rinse and towel off vigorously immediately after swimming

- Swim in the afternoon or early evening – the risk of swimmer’s itch is greatest before noon

- Avoid swimming during an onshore wind

- Swim in deeper water

- Have small children swim in a kiddy pool filled with well water rather than the lake

history of swimmer’s itch prevention tactics

Decades of research have proven that the most effective defense against swimmer’s itch is prevention, rather than control. By equipping Glen Lake residents and visitors with swimmer’s itch prevention strategies, we can arm the community against exposure.

Historically, the Glen Lake Association attempted to prevent swimmer’s itch by trying to break the lifecycle of the parasite host. From the 1950’s to the 1980’s, we sought to eliminate snail hosts using copper sulfate treatment. Yet, the snails repopulated as the chemical treatment expired – about two hours after treatment.

We then spent nearly three decades attempting to harass, trap, and relocate resident Common Mergansers which we believed were the only avian parasite hosts on the lake. Despite these removal tactics, cases of swimmer’s itch and the number of Mergansers on Glen Lake actually increased.

New DNA research conducted from 2017 to 2019 identified additional parasite hosts, including the Canadian Goose and Mallard Duck. This research revolutionized our scientific understanding of swimmer’s itch. It became clear that continuing to attempt to control swimmer’s itch on a lake-wide basis is ineffectual and a waste of precious resources. In addition, we were concerned about the long-term impact of a sustained trapping and removal program on the Glen Lake ecosystem.

What is the glen lake association doing to prevent swimmers itch now?

The Glen Lake Association remains vigilant in its efforts to study and research the most effective approaches for combating swimmer’s itch.

We will continue to educate the public about best practices for swimmer’s itch prevention based on available research and scientific evidence. Ongoing research, including the use of data from individual case reporting, will be key to furthering our ability to “combat the itch!”

*CDC Disclaimer

The use of Center for Disease Control (CDC) sourced materials does not imply any endorsement of the CDC, ATSDR, HHS, USDA, or the United States Government of Glen Lake Association (GLA), or any other organizations or any staff members or associates of GLA. Reference to specific commercial products, manufacturers, companies, or trademarks does not constitute its endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.