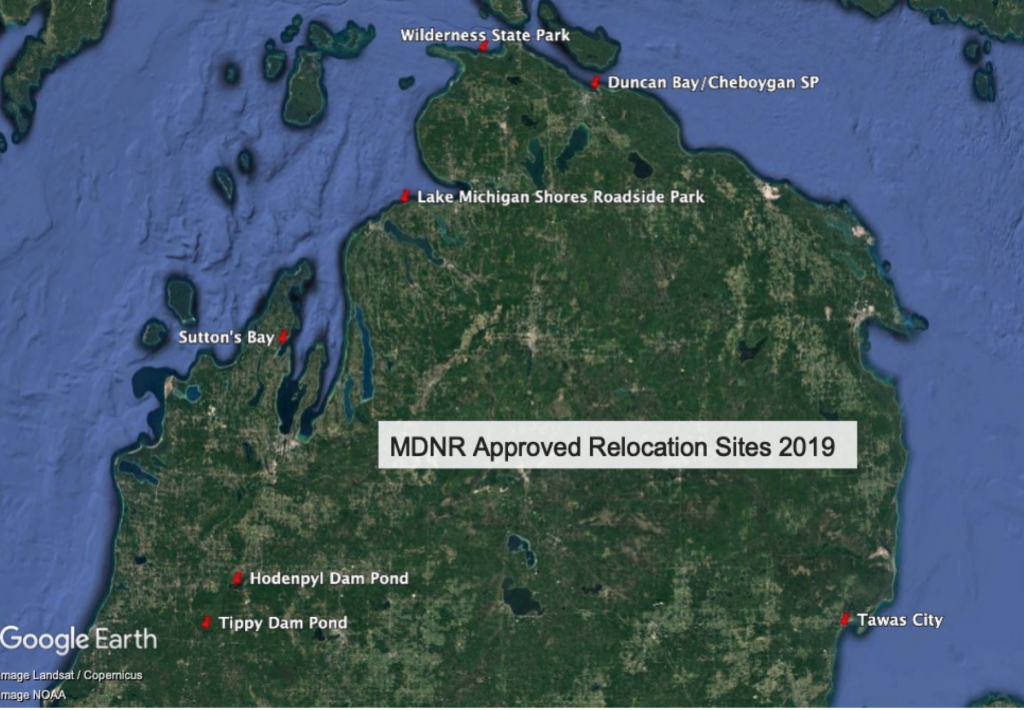

It has been widely accepted by many Swimmer’s Itch scientists that once Common Mergansers (once thought to be the major player in Swimmer’s Itch on Glen Lake) were live trapped and ready for relocation, that the approved DNR relocation sites were “safe” places to set the trapped birds free. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) approved relocation sites based on four principles:

- New area is not a good swim area;

- Site is free of the snail species that carries the parasite that cycles through Common Mergansers;

- Not a place where the DNR fisheries were planting fish;

- Suitable for Common Merganser survival

The 2019 Swimmer’s Itch research has now confirmed that many of the relocation sites have been tested “positive” for the species of parasite that cycles through Common Mergansers! This is bad news for the Swimmer’s Itch control program because it likely means that relocating Glen Lake mergansers to relocation sites that already have the parasite will only increase—perhaps dramatically—the itch risk for swimmers near the relocation sites. This new discovery presents a new ethical dilemma for the GLA and other lake associations around the state that use live trapping strategies.

One would think that a simple solution to this dilemma would be to find new sites that meet the DNR criteria where the parasite is not present. This may be a solution, but in the opinion of the local experts, there are likely “no new sites” to be found. Also, new discoveries have shown that relocated mergansers travel up to 20 miles once they are set free.

Old Assumptions, New Thinking

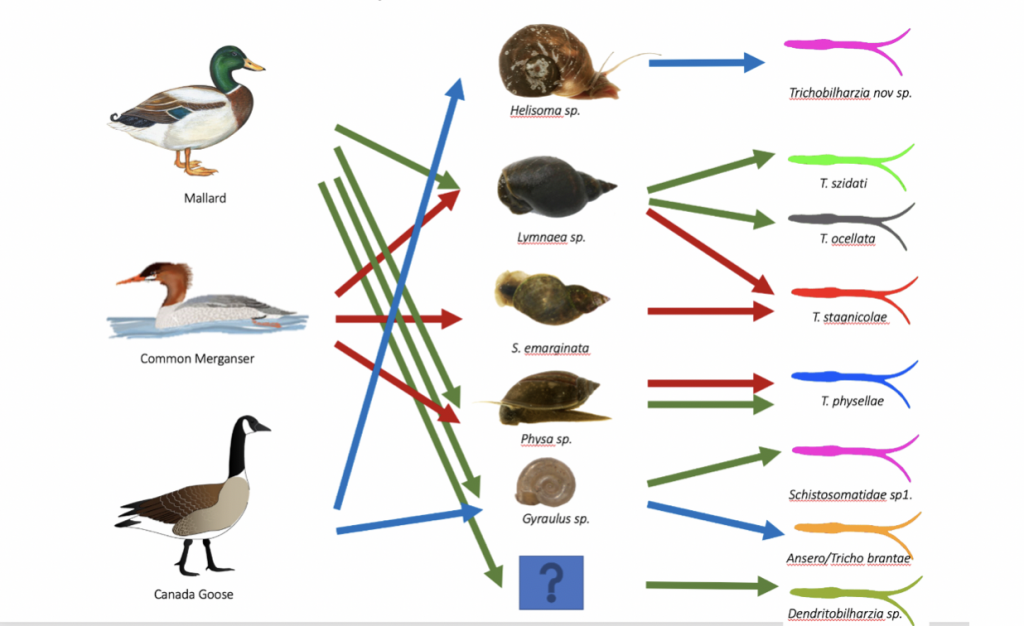

Just a few years ago, it was thought that almost all of itch-causing worms came from Common Mergansers, with other birds like Mallards and Canada Geese only minor contributors. It was standard thinking, therefore, to assume that removing Common Mergansers from Glen Lake would have a major impact on reducing itch risk.

However, 2019’s research on Swimmer’s Itch shows that Mallards and Canada Geese contribute to the parasite load in percentages higher than imagined. The mix of Swimmer’s Itch parasites from all the birds collectively contributes to increasing itch risk.

New data also suggests that snail densities, which can directly impact itch risk, fluctuate significantly from year to year. For example, when certain species of snail densities are high and combined with high population densities of the bird host, then SI risk for that specific life cycle can be problematic in a given year and move to center stage while other life cycles either hold their own or diminish.

What does this mean for Glen Lake and our lake-wide effort to control Swimmer’s Itch? One thing is certain, the life cycle that is dominant one year may play a minor role in the next year, depending on snail density fluctuations and changing bird populations. This is a complex issue, with Mother Nature throwing in all kinds of twists and turns that make lake-wide control not only difficult but perhaps unattainable.

GLA will continually update you with new information as we receive it.

Recent Comments